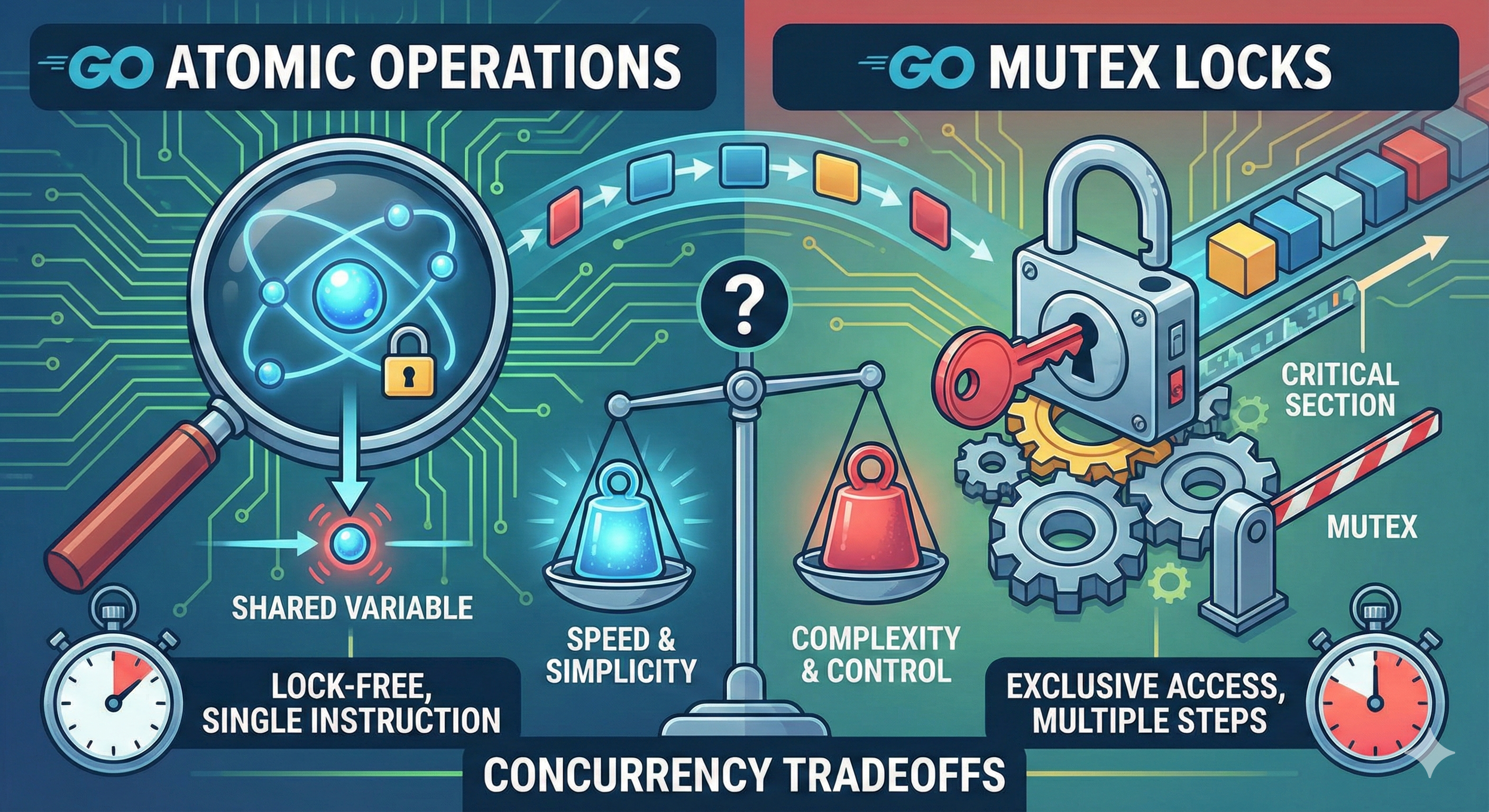

Go provides two primary mechanisms for safe concurrent access to shared memory: the sync/atomic package and sync.Mutex. Knowing when to use each can significantly impact both correctness and performance.

The Short Answer

Use atomic for simple counters and flags. Use mutex for everything else.

Atomic Operations

The sync/atomic package provides low-level atomic memory primitives. These operations are lock-free and typically compile down to single CPU instructions.

import "sync/atomic"

var counter int64

func increment() {

atomic.AddInt64(&counter, 1)

}

func get() int64 {

return atomic.LoadInt64(&counter)

}

Atomics are ideal when:

- You're working with a single primitive value (int32, int64, uint32, uint64, uintptr, pointer)

- The operation is simple: load, store, add, swap, or compare-and-swap

- Performance is critical and contention is high

Mutex

sync.Mutex provides mutual exclusion, ensuring only one goroutine can access a critical section at a time.

import "sync"

type SafeMap struct {

mu sync.Mutex

data map[string]int

}

func (m *SafeMap) Set(key string, value int) {

m.mu.Lock()

defer m.mu.Unlock()

m.data[key] = value

}

func (m *SafeMap) Get(key string) (int, bool) {

m.mu.Lock()

defer m.mu.Unlock()

v, ok := m.data[key]

return v, ok

}

Use a mutex when:

- You need to protect complex data structures (maps, slices, structs)

- Multiple fields must be updated atomically together

- The critical section involves multiple operations

The Performance Reality

Let's talk numbers. On modern hardware:

- Uncontended mutex: ~20-60 nanoseconds

- Atomic operation: ~4-8 nanoseconds

Atomics are faster, right? Not so fast. Under contention, the story flips. Atomics use spin-locks—they burn CPU cycles retrying until they succeed. Mutexes put goroutines to sleep and wake them when ready. At scale with many goroutines competing, sleeping is cheaper than spinning.

The real lesson: profile first, optimize second. I've seen teams rewrite mutex code to atomics chasing microseconds, only to create subtle bugs that cost days to debug.

The Correctness Trap

More importantly, atomics can be tricky to use correctly. Consider this buggy pattern:

// Bug: this is not atomic!

if atomic.LoadInt64(&counter) == 0 {

atomic.StoreInt64(&counter, 1)

}

Another goroutine can modify counter between the load and store. You'd need CompareAndSwap:

atomic.CompareAndSwapInt64(&counter, 0, 1)

With a mutex, the intent is clearer:

mu.Lock()

if counter == 0 {

counter = 1

}

mu.Unlock()

One more pitfall: never mix atomics and mutexes on related data. If you protect fieldA with a mutex and fieldB with atomics, you've created a synchronization nightmare. Pick one mechanism per logical group of data.

When Atomics Shine

Atomics excel in specific scenarios:

1. Simple counters with high contention

var requestCount int64

func handleRequest() {

atomic.AddInt64(&requestCount, 1)

// ... handle request

}

2. Boolean flags

var shutdown int32

func stop() {

atomic.StoreInt32(&shutdown, 1)

}

func isRunning() bool {

return atomic.LoadInt32(&shutdown) == 0

}

3. Configuration hot-swapping with atomic.Pointer

Go 1.19 introduced atomic.Pointer[T], which is perfect for swapping entire config objects without locks:

type Config struct {

MaxConns int

Timeout time.Duration

FeatureFlag bool

}

var currentConfig atomic.Pointer[Config]

func init() {

currentConfig.Store(&Config{MaxConns: 100, Timeout: 30 * time.Second})

}

// Readers never block

func GetConfig() *Config {

return currentConfig.Load()

}

// Writers swap the whole object

func UpdateConfig(new *Config) {

currentConfig.Store(new)

}

This pattern gives you lock-free reads while still maintaining consistency—readers always see a complete, valid config, never a half-updated struct.

4. Lock-free data structures (advanced)

If you're implementing lock-free queues or similar structures, atomics are essential. But this is expert territory—get it wrong and you'll have bugs that only manifest under load at 3am.

RWMutex: The Middle Ground

For read-heavy workloads, sync.RWMutex allows multiple concurrent readers:

type Cache struct {

mu sync.RWMutex

data map[string]string

}

func (c *Cache) Get(key string) (string, bool) {

c.mu.RLock()

defer c.mu.RUnlock()

v, ok := c.data[key]

return v, ok

}

func (c *Cache) Set(key string, value string) {

c.mu.Lock()

defer c.mu.Unlock()

c.data[key] = value

}

Summary

| Use Case | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Single counter/gauge | atomic |

| Boolean flag | atomic |

| Map or slice | Mutex or RWMutex |

| Multiple fields updated together | Mutex |

| Read-heavy, write-light | RWMutex |

| Complex invariants | Mutex |

The Bigger Picture

One thing becomes obvious after enough real-world debugging: the whole "atomics vs mutexes" debate is almost never where your performance problems come from. I've gone deep on synchronization micro-optimizations, only to discover the real issues were N+1 queries, missing indexes, or broader architectural bottlenecks.

Atomics are a scalpel; mutexes are a full toolbox. And most of the time, you need the toolbox.

If you're unsure, reach for a mutex first. It's clearer to reason about, harder to misuse, and far more forgiving. If profiling later shows actual contention, then consider atomics or more advanced concurrency patterns. The fastest code is the code that's correct, stable, and running in production—not the "clever" version still being untangled in a debugger.