TL;DR

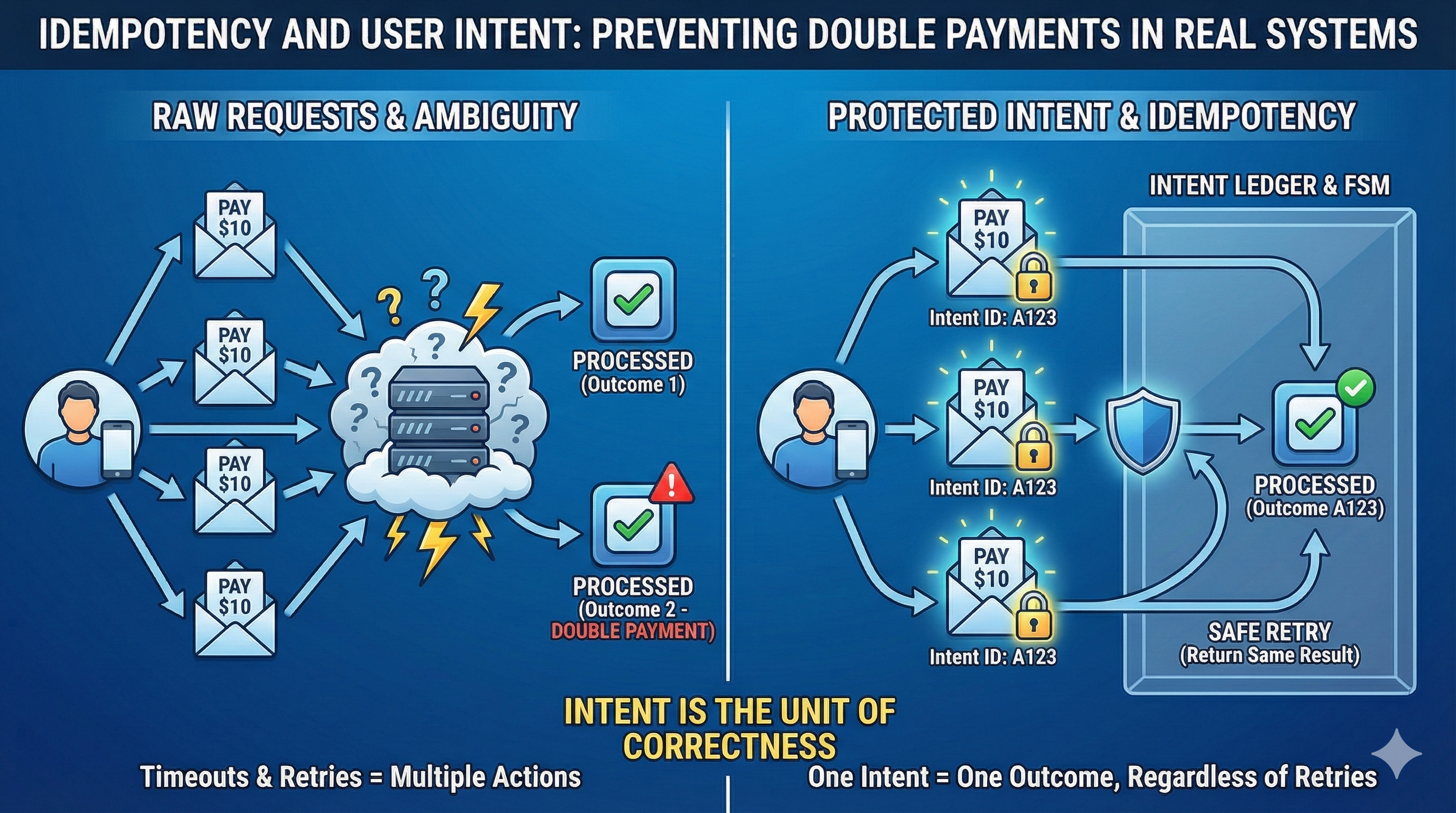

- Users express intent, not requests

- Retries are attempts to express the same intent

- Double payments happen when systems treat retries as new actions

- Idempotency protects intent, but only with atomicity and durability

- Exactly-once delivery is not enough

- Model intent and its progress explicitly, and retries become boring

Preventing double payments isn't about exactly-once delivery. It's about protecting user intent through retries, timeouts, and crashes.

1. The Problem Users Actually Care About

Users don't care about delivery guarantees or message brokers.

They care about one thing:

Did I just pay once — or twice?

Double payments happen under normal conditions:

- a user double-clicks a payment button

- a client retries after a timeout

- a backend retries after a transient failure

- an event is delivered twice

- a process crashes after a side effect but before acknowledgment

In every case, the user intent is the same: one action, one payment.

Most double-payment bugs aren't exotic. They come from normal retries and partial failures in systems that confuse requests with intent.

2. How Double Payments Really Happen

Double payments come from ambiguity.

A typical pattern looks like this:

- A user initiates a payment

- The system begins processing

- A failure occurs — timeout, crash, slow dependency

- The user or client retries

- The system processes the retry as a new action

To the system, both requests are valid. To the user, there was only one intent.

After a timeout or crash, the system can't tell whether the first attempt succeeded, failed, or is still in progress. When it treats each retry as a new action, double execution becomes inevitable.

Queues, transactions, and delivery guarantees don't solve this on their own. They don't model why the request exists.

The failure isn't technical. It's conceptual: the system has no way to recognize when multiple requests express the same user intent.

3. A Concrete Example: A Payment Retry Gone Wrong

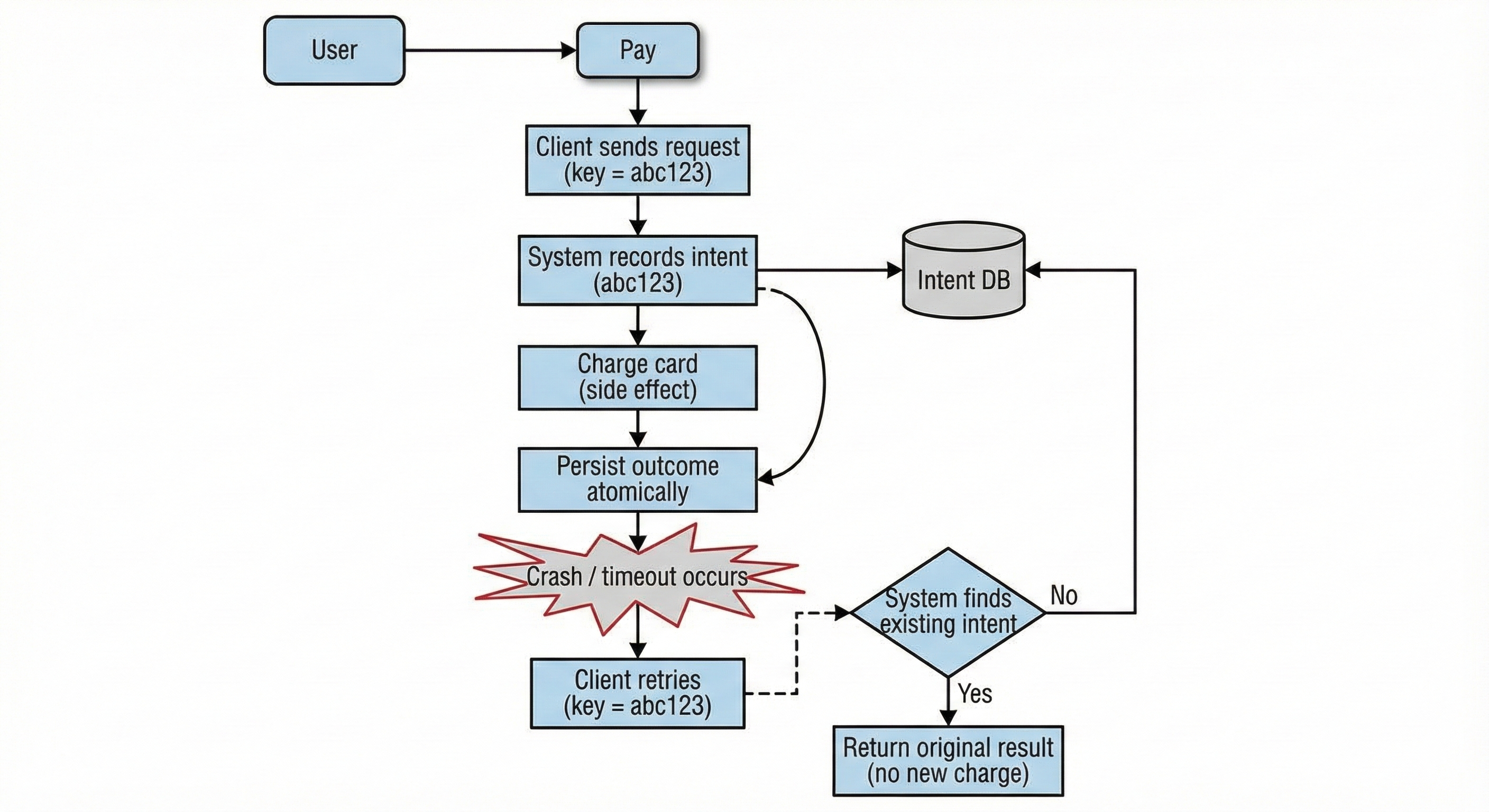

Consider a simple payment flow:

- The client sends a

POST /paymentsrequest - The backend charges the card

- The backend crashes before responding

From the client's perspective, the request timed out. It retries.

If the system treats this retry as a new payment:

- the card is charged again

- both requests look valid

- nothing "failed" technically

But from the user's perspective, they paid once.

A system built around intent behaves differently:

- the first request records an intent with a unique idempotency key

- the charge and the recorded outcome happen atomically

- when the retry arrives with the same key, the system recognizes the intent

- instead of charging again, it returns the original result

The retry doesn't create new work. It re-enters existing work.

Payment Retry Flow (Intent-Aware)

This is the difference between retrying a request and re-entering an intent.

4. User Intent Is the Unit of Correctness

Requests are not intent.

Requests are attempts to express intent, and under failure they are inherently ambiguous.

Intent is the decision the user made: "I want to pay this amount once."

Correct systems treat user intent, not individual requests, as the unit of correctness. Multiple requests are allowed to represent the same intent.

If a system cannot answer:

"Have I already acted on this user's intent?"

then retries, crashes, and partial failures will always be dangerous.

5. Idempotency as Intent Protection

Idempotency isn't just "handling duplicates." It's intent protection.

Idempotency keys are intent identifiers.

A key identifies what the user meant, not how many times they asked.

When a client retries with the same key, it is saying:

"This is still the same action. Please don't do anything new."

Correct behavior is not to reject the retry, but to return the same outcome.

Idempotency doesn't prevent retries. It makes retries harmless.

But it only works if the system is built for it.

6. Foundations: Atomicity and Durability

Idempotency depends on two non-negotiable foundations.

Atomicity

Recording user intent and recording the outcome of that intent must happen atomically.

If a system:

- performs side effects first, and

- records intent or results later

then crashes introduce ambiguity that retries cannot safely resolve.

Idempotency without atomicity is wishful thinking.

Atomicity doesn't require a single database. It requires that intent and outcome are never observed independently.

Durability

User intent must survive failures.

If intent disappears when a process crashes, a service restarts, or a deployment rolls, retries become new actions.

Durability lets the system say:

"I've already seen this intent — and here is what happened."

Once intent is durable and transitions are atomic, the remaining problem is progress: how an intent moves safely through the system.

7. Modeling Intent Progress

Now the real question: how does intent move forward over time?

Real systems solve this by explicitly modeling progress and allowing retries to safely re-enter at any point.

Two patterns appear repeatedly.

Finite State Machines (FSMs)

An FSM models intent states and valid transitions.

For example:

- RECEIVED

- PROCESSING

- COMPLETED

- FAILED

Retries become safe re-entries:

- If COMPLETED, return the result

- If PROCESSING, continue or wait

- If FAILED, return the failure

FSMs only work if transitions and side effects are protected by atomicity — the system must never observe a state change without its associated outcome.

Append-Only Ledgers

Instead of mutating state, ledgers record events:

- IntentCreated

- FundsReserved

- FundsTransferred

- IntentCompleted

State is derived, not stored.

Ledgers are immutable, auditable, and replayable. Because events are durable and append-only, intent survives failures and idempotency becomes the default.

Hybrid Models

Most real systems combine both:

- FSMs for control flow

- Ledgers for truth and audit

FSMs control flow. Ledgers preserve truth.

8. Exactly-Once Delivery and Where Guarantees Stop

Messaging systems can offer exactly-once delivery.

They cannot offer exactly-once effects.

Brokers don't know user intent or which side effects already occurred. Their guarantees stop at the boundary of your application.

Even with exactly-once delivery:

- a process can crash after a side effect but before acknowledgment

- retries can re-enter the system

- business logic can still execute more than once

Exactly-once delivery can reduce noise. It cannot replace intent-aware design.

This isn't a theoretical problem.

Payment providers like Stripe explicitly require idempotency keys because retries, timeouts, and ambiguous outcomes are normal at scale. Their APIs assume the same intent may be expressed multiple times, and correctness depends on recognizing it¹.

Historically, systems that failed to model intent explicitly — including early large-scale payment platforms such as PayPal — experienced duplicate charges and delayed reversals under retry-heavy failure conditions. These incidents weren't caused by "bugs" so much as ambiguity: the system couldn't reliably tell whether a payment had already succeeded².

Modern payment systems treat intent as a first-class concept precisely because exactly-once delivery is not something the real world provides.

9. Designing for Intent

Thinking in terms of intent changes how systems are designed.

I don't ask how to make requests safe. I ask:

- how intent enters the system

- how progress is tracked

- how ambiguity is resolved under failure

That usually leads to:

- explicit intent identification

- atomic state transitions

- modeled progress

- retries that are safe by default

Once those are in place, idempotency stops being a special case. It becomes a natural property of the system.

10. Industry Patterns for Reliable Messaging

The principles above — intent modeling, atomicity, and durability — show up in well-established patterns across the industry. Future articles will explore these in depth, but here's a brief overview.

The Transactional Outbox Pattern

When a service needs to update its database and publish an event, it faces a dual-write problem: if the database write succeeds but the message publish fails (or vice versa), the system becomes inconsistent.

The Outbox pattern solves this by writing both the business data and the outgoing message to the database in the same transaction. A separate relay process reads the outbox table and publishes messages to the broker. Because both writes are atomic, consistency is guaranteed — even if the relay crashes and republishes, downstream consumers handle duplicates via idempotency.

The Transactional Inbox Pattern

The inverse problem: when a service receives events, how does it ensure each event is processed exactly once?

The Inbox pattern stores incoming events in an inbox table before processing. Before handling an event, the service checks whether it has already been processed (using the event ID). If so, it skips reprocessing. This protects against duplicate delivery from the message broker and makes consumption idempotent by default.

When message ordering matters, the inbox can also restore order using monotonically increasing identifiers — holding messages until gaps are filled.

State-Based Idempotency

This is the pattern we explored in section 7 with finite state machines. Rather than tracking request IDs in a separate table, state-based idempotency uses the entity's current state to determine whether an operation should proceed.

If a payment is already COMPLETED, a retry doesn't need to check an idempotency key table — the state itself tells the system the work is done. The operation becomes a no-op that returns the existing result.

This approach works well when:

- The entity has a clear lifecycle with terminal states

- State transitions are atomic and durable

- The "work" is inherently tied to moving between states

State-based idempotency is often simpler than key-based approaches because there's no separate bookkeeping — the business data is the idempotency record.

Timeouts, Retries, and the Real World

Sam Newman's talk Timeouts, Retries and Idempotency in Distributed Systems³ captures the practical reality well: you can't beam information instantaneously, sometimes you can't reach what you need, and resources are finite.

Key takeaways:

- Timeouts mean giving up — but after a timeout, you don't know if the request succeeded, failed, or is still in progress

- Retries mean trying again — but without idempotency, retries become new actions

- Idempotency is easy to implement upfront, but hard to retrofit

Newman recommends unique request IDs to track operations and warns against aggressive retry strategies that compound failures. The patterns described in this article — intent modeling, atomic transitions, and durable state — are what make retries safe.

Upcoming articles will dive deeper into implementing the Outbox and Inbox patterns, including CDC-based approaches, failure modes, and practical tradeoffs.

11. Closing

Double payments don't happen because systems retry.

They happen because systems confuse attempts with intent.

Model intent. Make progress explicit. Protect transitions with atomicity.

Do that, and retries become boring.

Footnotes

1. Stripe API Documentation — Idempotent Requests: stripe.com/docs/api/idempotent_requests

2. Public discussions and incident analyses of early PayPal retry and duplicate charge behavior under network failures, including Hacker News engineering discussions on payment idempotency and retries. Example: Ask HN: Why do payment APIs require idempotency keys?

3. Sam Newman — Timeouts, Retries and Idempotency in Distributed Systems: infoq.com/presentations/distributed-systems-resiliency